PARIS - The Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, popularly known by its initials CNRS, is France's premier research institute. Fully funded by the government, it is a huge organisation with sections that conduct scientific research in various disciplines, including the humanities. The seven-member team at CNRS that studies Nepal is a small part of a section devoted to the study of the societies and cultures of the Himalaya.

PARIS - The Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, popularly known by its initials CNRS, is France's premier research institute. Fully funded by the government, it is a huge organisation with sections that conduct scientific research in various disciplines, including the humanities. The seven-member team at CNRS that studies Nepal is a small part of a section devoted to the study of the societies and cultures of the Himalaya. But the relatively small size of the team working on Nepal section is rather deceptive. Every member is a hardcore Nepal enthusiast and knows more about our country than many of us do back home in Kathmandu. One of them is Philippe Ramirez, who has a Nepali calendar featuring Madan Bhandari on the wall above his desk, and who is compiling a genealogy of the Koiralas and has studied in detail all the Bhusal family feuds.

In another corner, Marie Lecomte-Tilouine is typing up a paper on kingship in Nepal, which she has been asked to present at a seminar on the royal houses of the world. She is an authority of sorts on Magars and talks so fondly about her days in the country that you would be forgiven for assuming that her maiti was somewhere in the hills of mid-western Nepal. Whenever in doubt about the proper equivalent in English for a French expression, she unconsciously lapses into chaste Nepali, often surprising me with her choice of word. Another trio of researchers is waiting for things to settle down a bit before they can resume fieldwork in Dailekh. These are all the real pros of the academic world. I have to be on my guard constantly to ensure I don't make a fool of myself. One slip of the tongue, and the shallowness of my journalese could be exposed.

Marie is presently reading Bir Charitra, an old Nepali book published by Jagadamba Prakashan. At my surprise that she reads Nepali with such fluency, she says bluntly, "You can't pretend to know Nepal without reading Nepali. Despite what you write, the English press and the English books on Nepal barely scratch the surface. To get a feel of the undercurrents, one has to dive deep into Nepali language publications, not only from Kathmandu, but from outside the Valley as well." Now that is something which many western scholars studying Nepal fail to realise even after spending years poring over Hamilton, Kirkpatrick, Leo Rose and Hrishikesh Shah. Looking at the surface is reassuring-it reflects your own image. Even scholars are charmed when they find that their \'research' merely confirm their biases.

The sole Nepali member of the team at the CNRS is Mahesh Khakurel, and everyone agrees that he is more French than most French scholars at CNRS. Mahesh speaks upper-class French with the right accent, is a connoisseur of French wines, and concocts the cuisine with such style that he could put some of the best French chefs to shame. Mahesh, who is working on his doctoral thesis, has lived in France for almost a decade and has contacts in the highest corridors of power in Paris.

By Nepali standards, Mahesh is remarkably well-off. But I sense a trace of melancholy in his voice when he says, "Life here is without meaning. You wait for death by living in comfort." Is he merely repeating the existential dilemma of Albert Camus, another Parisian, ("Rising, street-car, four-hours in the office or factory, meal, street-car, four-hours at work, meal, sleep, and Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday according to the same rhythm")? Or is his search for meaning representative of the frustrations of otherwise successful Nepalis living abroad? I have no way of knowing, but if the impotent rage of NRNs (Non-Resident Nepalis) writing letters to the editor of this paper are any indication, the Nepali diaspora does seem to lack an anchor. Mahesh has found a constructive outlet for his anger-he runs an organisation in Paris that channels funds to the impoverished schools of the Nepali countryside.

The charged atmosphere at the CNRS Nepal section puts me in mind of the stale air of the almost moribund CNAS (Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies) at Tribhuvan University. How many of our so-called India experts pursue the Dainik Jagaran, Aaj, Amar Ujala, or the Rastriya Sahara published from Patna, Gorakhapur, Varanasi and Bareilly, respectively?

That apart, we in Nepal seem to have given the miss to producing knowledge. As in things all else, we have become mere consumers of ideas. Even the few academics that we have pursuing research in the social sciences often follow the agenda of donors funding their project. They are-as some of their own breed call them behind their backs-intellectual bharias carrying the load for researchers from abroad. In the long term, such intellectual subservience can turn out to be even more damaging than aid dependence in our economy.

Marie shares my gloom about social science research in Nepal-or lack thereof. She says that most social research in Nepal these days is carried out by journalists. That may not be so bad in the short term, but this trend is not sustainable. Journalists tend to be generalists and often lack the rigours of academic discipline, and tend to be too involved in "here-and-now" to be dispassionate about events and trends. Catch-phrases and sound-bites are fine even for reporting that strives to be factual and fair, but deeper analyses need the kind of patience and persistence that only a researcher has, free from the pressures of deadlines and space-restrictions. No wonder, then, that six years into the insurgency not one substantive work on the Maoist movement in Nepal has emerged from Kathmandu. Academics have been writing opinion pieces in the manner of columnists.

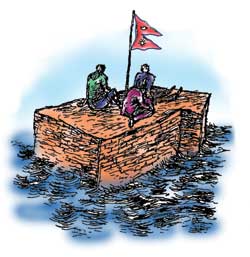

Marie shares my gloom about social science research in Nepal-or lack thereof. She says that most social research in Nepal these days is carried out by journalists. That may not be so bad in the short term, but this trend is not sustainable. Journalists tend to be generalists and often lack the rigours of academic discipline, and tend to be too involved in "here-and-now" to be dispassionate about events and trends. Catch-phrases and sound-bites are fine even for reporting that strives to be factual and fair, but deeper analyses need the kind of patience and persistence that only a researcher has, free from the pressures of deadlines and space-restrictions. No wonder, then, that six years into the insurgency not one substantive work on the Maoist movement in Nepal has emerged from Kathmandu. Academics have been writing opinion pieces in the manner of columnists. Depending on foreign aid for our economic development has its flip side-it gives birth to a class of neo-rich that doesn't care much about its social obligations. There is much to fear direct foreign investment in media-it may turn newspapers into products peddling illusions. Inviting foreign troops to fight our \'war' is close to hara-kiri-a nation saved by others automatically becomes subservient towards its saviour. But most dangerous of all this is intellectual servitude. A nation that cannot think independently cannot guard its independence for long.