Why does the National Centre for AIDS and STD Control report only 2,097 HIV-positives in Nepal, whereas the UNAIDS/WHO estimate for the end of 2000 was 34,000? Several recent articles have noted the discrepancy and criticised the National Commission on AIDS and STD Control (NCASC) for "getting it wrong".

Why does the National Centre for AIDS and STD Control report only 2,097 HIV-positives in Nepal, whereas the UNAIDS/WHO estimate for the end of 2000 was 34,000? Several recent articles have noted the discrepancy and criticised the National Commission on AIDS and STD Control (NCASC) for "getting it wrong". This is very unfair. NCASC\'s monthly statistics depend on tests reported to it. These are complete and accurate as far as reporting goes. But there are a lot of reasons HIV-positives are not reported:

- "I feel well, why should I go for a test?" Many HIV-positive people do not suspect they are positive because generally there aren\'t recognisable symptoms for five, even 10 years.

- "I might be better not knowing if I am HIV-positive." People who think they may be infected may not wish to have a test because of social stigma and misunderstandings.

- "Where would I go?" There are not many centres where HIV antibody testing can be done in Nepal.

- Some testing centres do not make full reports to NCASC.

Nepal is not alone in having such statistical discrepancies. There is underreporting in most countries of the world. So where does UNAIDS get its figure of 34,000? The answer is complex and the science of estimating HIV numbers is far from precise. But it is based on several sources of information. UNAIDS can get figures from "sentinel surveillance", which consists of anonymous HIV testing at selected "Sentinel Sites". These may be antenatal clinics, sexually transmitted disease clinics, TB clinics and blood donation centres. Some countries test at military recruiting.

Or, it may be based on reports from special studies, for example in sex workers, transport workers, migrant labourers and injecting drug users. And then there are the cases reported to the National Centre.

Using these measures, an estimate of 34,000 HIV positives was made a year ago, giving a prevalence rate of a bit under 0.3 percent in the age group 14-49. On this basis, Nepal is defined as having a "concentrated epidemic" of HIV. This means the prevalence of HIV in adults is less than 1 percent, but, according to special studies, HIV is present in over 5 percent in certain sub groups of the population. These groups are injecting drug users (up to 50 percent), sex workers (up to 18 percent) and, in a very small study, migrant labourers (10 percent). Needless to say, these people are the least likely to have HIV tests that are reported to NCASC.

A concentrated epidemic is bad for infected sub-groups, but not so bad for the rest of the population. But Nepal and other Asian countries are a relatively early stage in the epidemic. Clients of sex workers, including migrant labourers, could form a "bridge" to the general population, leading to a generalised epidemic.

The UNAIDS prediction is that by 2010, the prevalence of HIV in Nepal will be 1-2 percent, there will be 10,000 to 15,000 AIDS cases and AIDS will be the commonest cause of death in the 15-49 age group. AIDS deaths, currently 3000 per year, are predicted to reach more than 6000 per year by 2005.

Will these predictions come true? Changes in a whole range of socio-economic and human behaviour could make the reality better or worse, such as:

- The number of men visiting sex workers, including men who go abroad as migrant labourers and visit sex workers there.

- The number of other women with whom they have sexual relations in Nepal, that is, the size of their "sexual networks".

- The number of men with whom the women have sexual relations, for example when their husbands are away from home.

- The increase or decrease of the sex industry in Nepal.

- The sexual interactions of injecting drug users with sex workers and the general population. This is another "network".

- The success or failure of "harm reduction" initiatives, especially condom use in sex workers and needle exchange in drug users.

Of course, we cannot predict how the behaviour of the population will change in the future. Will there be further liberalisation of attitudes to sex, increasing sexual networks and a disregard of the consequences of unprotected sex? If so, the predictions above will be exceeded. Will people grasp the risk factors and look for ways to protect themselves and their families? If so, the HIV situation will not be so bad as predicted.

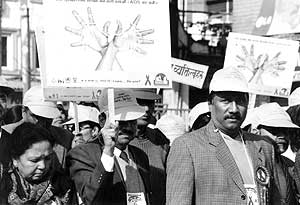

What can be done and who should do it? Ultimately, only we can change our behaviour. The responsibility lies with each one of us. But there is a good deal that the government and non- governmental organisations can do, both to help those already affected and to prevent the virus from spreading.

In early October this year, there was an International Conference on AIDS in Asia and the Pacific in Melbourne. Associated with it was a Ministerial Level meeting at which the Health Minister and Home Minister represented Nepal. A Western correspondent who clearly did not know Nepal was surprised to find the Nepal\'s Health Minister surrounded by about 50 Nepali delegates and engaged in deep discussion about what the government should do. Not so surprising? Well, it was an unusual sight in Australia, because they were all sitting in the floor!

Whether from the floor or from the Ministerial Meeting chamber, the Ministers seem to have got the message. By all accounts they have returned to Nepal determined to make the effort to prevent the spread of the HIV virus. They cannot succeed alone. At all levels, from the personal to the political, it depends on us.

(Dr Dickinson is director of the United Mission Nepal's AIDS Sakriya Unit)

HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus. It spreads by sexual contact, infected blood and from an infected pregnant woman to her child.

AIDS: Acquired Immuno-deficiency Syndrome. The disease resulting from HIV infection after some years. The virus slowly destroys the immune system, which protects the body against infections and some cancers.