The deployment of Gurkha soldiers in Afghanistan is a possibility as British commandos in Oman go on standby this week. The last time the Gurkhas were in action in Afghanistan was in the disastrous British retreat from Kabul almost exactly 160 years ago.

The deployment of Gurkha soldiers in Afghanistan is a possibility as British commandos in Oman go on standby this week. The last time the Gurkhas were in action in Afghanistan was in the disastrous British retreat from Kabul almost exactly 160 years ago. As Peter Hopkirk explains in The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia, in the 1830s, the exiled Shah Shujah was itching to depose the ruler of Afghanistan, Dost Mohammad and regain the throne. The British decided that they wanted to move further north in their attempts to reconnoitre hitherto unmapped routes between India and Russia across the Hindu Kush. But to do this, they needed a friendly ruler in Kabul-and Dost Mohammad was not.

For the next few years there was all manner of Great Game intrigue, the British admonishing Dost Mohammad as if he were "a naughty schoolboy", and the Russians using this rift to inveigle themselves into the court. Shah Shujah needed to be pacified and returned to Afghanistan so he would give up his claims to Peshawar.

In 1838-39, the First Afghan War broke out, and Shah Shujah was restored to the throne in Kabul. During the campaign he ordered executions cruel even by frontier standards and, once his authority was established through fear, made the public feed his army and raised taxes to support his lavish lifestyle. None of this brought him any goodwill, and also gave rise to great resentment against his British sponsors.

These years were not just a time of Anglo-Russian rivalry over passage through Central Asia and the establishment of Afghanistan as a pro-British buffer between India and the Tsar's territory-Afghanistan and the \'khanates' of the region were all absorbed in their own rivalries. One of the results of this was that Dost Mohammad's favourite son, Mohammad Akbar Khan, lived across the border in Turkestan, whose internal politics were a matter of some interest to Afghanistan, Britain and Russia. He lived there until 1841, when things came to a head.

There were riots in Kabul and a prominent British diplomat, Alexander Burnes, was cut to pieces. Mohammad Akbar Khan-Akbar-came back to lead what had turned into a full-scale insurrection against the British and their puppet ruler. In the war that followed, two British men played prominent roles-Sir William Macnaghten, a former political secretary in Calcutta and a brilliant Orientalist and polyglot, said to be as fluent in Farsi, Arabic and Hindustani as he was in English, and General William Elphinstone, the officer in charge of British troops outside Bala Hissar, the walled citadel overlooking the capital.

The British were routed and some 16,000 British troops and civilians started back to Jalalabad, the nearest British garrison. Five days later, between relentless Afghan firing and exposure to the bitter cold, all but a handful of the troops and over two-thirds of the civilians were dead. Following are excerpts from Hopkirk's account of the disastrous encounter, in some part based on historian John Kaye's History of the War in Afghanistan:

In the cantonments, meanwhile, things were going from bad to worse. News was coming in of the fall of outlying British posts to the rebels, with considerable loss of life, including the massacre of an entire Gurkha regiment. A number of officers had been killed and others wounded, among them Major Eldred Pottinger, the hero of Herat. The cruel Afghan winter had already begun, far earlier than usual, and food, water, medicines and morale were beginning to run low. So too, it appears, was courage, for the garrison's one and only major assault on the rebels had ended in a humiliating and costly defeat which saw the headlong flight of the British and Indian troops back to their own lines. Kaye was to call it \'disgraceful and calamitous'. It took place on 23 November, when the Afghans suddenly moved two guns to the top of a hill overlooking the British position and began to bombard the crowded camp below.

In the cantonments, meanwhile, things were going from bad to worse. News was coming in of the fall of outlying British posts to the rebels, with considerable loss of life, including the massacre of an entire Gurkha regiment. A number of officers had been killed and others wounded, among them Major Eldred Pottinger, the hero of Herat. The cruel Afghan winter had already begun, far earlier than usual, and food, water, medicines and morale were beginning to run low. So too, it appears, was courage, for the garrison's one and only major assault on the rebels had ended in a humiliating and costly defeat which saw the headlong flight of the British and Indian troops back to their own lines. Kaye was to call it \'disgraceful and calamitous'. It took place on 23 November, when the Afghans suddenly moved two guns to the top of a hill overlooking the British position and began to bombard the crowded camp below. Even General Elphinstone, who until now had expended more energy quarrelling with Macnaghten than in engaging the enemy, could not ignore this threat. He ordered a far from enthusiastic brigadier to venture forth with a force of infantry and cavalry. Having successfully seized the hill and silenced the guns, the brigadier turned his attention to the enemy held village below. It was here that things began to go wrong There had long been a standing order that guns must always move in pairs, but for some reason, perhaps to give himself greater mobility, the brigadier had only taken one 9-pounder with him. At first the grape-shot from this had had a devastating effect on the Afghans occupying the village, but soon it began to overheat, putting it out of action when it was most needed. As a result the attack on the village was driven back. Meanwhile the Afghan commanders had dispatched a large body of horsemen and foot-soldiers to the assistance of their hard-pressed comrades. Seeing the danger, the brigadier at once formed his infantry into two squares, massing his cavalry between them, and waited for the enemy onslaught, confident that the tactics which had won the Battle of Waterloo would prove as deadly here.

But the Afghans kept their distance, opening up a heavy fire on the tightly packed British squares with their long-barrelled matchlocks, or jezails. To the dismay of the brigadier's men, easy targets in their vivid scarlet tunics, their own shorter-barrelled muskets were unable to reach the enemy, the rounds falling harmlessly short of their targets. Normally the brigadier could have turned his artillery on the Afghans, causing wholesale slaughter in their ranks, whereupon his cavalry would have done the rest. However, as Kaye observed, it seemed as though \'the curse of God was upon those unhappy people', for their single 9-pounder was still too hot for the gunners to use without the risk of it exploding, and in the meantime men were falling in scores to the Afghan marksmen. Then, to the horror of those watching the battle from the cantonments far below, a large party of the enemy began to crawl along a gully towards the unsuspecting British. Moments later they broke cover and flung themselves with wild cries upon their foes, who promptly turned and fled. Desperately the brigadier tried to rally his men, displaying remarkable courage in facing the enemy single-handed, while ordering his bugler to sound the halt. It worked, stopping the fleeing men in their tracks. The officers re-formed them, and a bayonet charge, supported by the cavalry, turned the tide, scattering the enemy. By now the 9-pounder was back in action, and the Afghans were finally driven off with heavy casualties.

The British triumph was short-lived, though, for the Afghans were quick to learn their lesson. They directed the fire of their jezails against the unfortunate gunners, making it all but impossible to use the 9-pounder: At the same time, from well out of range of the British muskets, they kept up a murderous hail against the exhausted troops, whose morale was once more beginning to crumble. It finally gave way when a party of Afghans, again crawling unseen up a gully, leaped unexpectedly upon them with blood-curdling screams and long, flashing knives, while their comrades kept up an incessant fire from near-invisible positions behind the rocks. This was too much for the British and Indian troops. They broke ranks and fled back down the hill all the way to the cantonments, leaving the wounded to their inevitable fate.

The weather was now rapidly deteriorating, and they had little time to waste if they were to stand a chance of getting through the passes to Jalalabad before they were blocked for the winter. Pottinger was given no choice but to submit to most of Akbar's harsh demands. On 1 January, 1842, as heavy snow fell on Kabul, an agreement was signed with Akbar under which he guaranteed the safety of the departing British, and promised to provide them with an armed escort to protect them from the hostile tribes through whose territories they must pass. In return, the British agreed to surrender all but six of their artillery pieces and three smaller mule-borne guns. For their part, the Afghans dropped their demand for married officers with families to stay behind, and Captain Mackenzie and his companion were freed. The first they had known of Macnaghten's fate was when his severed hand, attached to a stick, was thrust up in front of the window of their cell by a mob yelling for their blood outside. Instead of them, as a guarantee of good faith, Akbar insisted that three other young officers stay behind as their \'guests'. The \'British were in no position to argue.

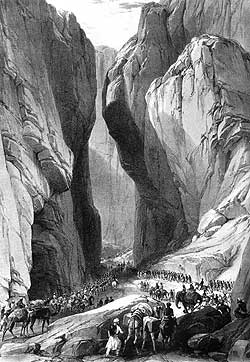

At first light on 6 January, to the sound of the bugles and drums, and leaving Shah Shujah and his followers to fend for themselves inside the Bala Hissar, the once proud Army of the Indus marched ingloriously out of the cantonments. Its destination was Jalalabad, the nearest British garrison which lay more than eighty miles across the snow-covered mountains to the east. From there it would leave Afghanistan and enter India by the Khyber Pass. Leading the march was an advance guard of 600 red-coated troops of the 44th Regiment of Foot and 100 cavalry. Next came the British wives and children on ponies, and sick or pregnant women in palanquins borne by Indian servants. Then followed the main body of infantry, cavalry and artillery. Last of all came the rearguard, also consisting of infantry, cavalry and artillery. Between \'the main body and the rearguard wound a long column of camels and bullocks carrying ammunition and food. Left to struggle along as best they could, without any proper provision having been made for them, were several thousand camp-followers who attached themselves to the column wherever they could.

So it was, on that icily cold winter's morning, that the long column of British and Indian troops, wives, children, nannies, grooms, cooks, servants and assorted hangers-on-16,000 in all-set out through the snow towards the first of the passes.

A week later, shortly after noon, a look-out on the walls of the British fort at Jalalabad spotted a lone horseman in the far distance making his way slowly towards them across the plain. News of the capitulation of the Kabul garrison had already reached Jalalabad, causing intense dismay, and for two days, with increasing anxiety, they had been expecting the advance guard. For it was a march which normally took only five days. At once the look-out raised the alarm, and there was a rush for the ramparts. A dozen telescopes were trained on the approaching rider. A moment later someone cried out that he was a European. He appeared to be either ill or wounded, for he leaned weakly forward, clinging to his horse's neck. A chill ran through the watchers as it dawned on them that something was badly amiss. \'That solitary horseman', wrote Kaye, \'looked like the messenger of death.' Immediately an armed patrol was sent out to escort the stranger in, for numbers of hostile Afghans were known to be roaming the plain.

Excerpted from The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia, Peter Hopkirk, 1990, Oxford University Press, Rs 500.