Day 1: The road

I woke early in the plush confines of a five-star hotel in Kathmandu, overly refreshed and raring to go after a forced layover in my own city hoping another day wouldn't be sacrificed to the whims of the fog-god of Delhi, so I could make it, albeit late, to the Jaipur Literature Festival.

And as I waited in line to swap Jet Lite for Nepal Airlines ("they fly in minimum visibility, don't worry," a friend at another carrier assured me); to board in the thronging crowds ("last month a Korean lady suffocated here it was so packed they said it was a heart attack," he continued); and boarded the plane, I realised I was actually going to make it.

But the waiting wasn't over. On the plane (the air hostess remonstrated with some young louts fiddling with the emergency door until indignant passengers demanded they be moved); on the runway on Delhi ("there's a traffic jam, we could be here for an hour," Capt. Shrestha announced); in line at immigration (scores of imposing Afghan men and delicate, fair girls were processed at harp speed before us); and finally in the baggage halls of Delhi's gleaming new airport...all this while, all this while, the Jaipur Literature Festival growled and purred its way into top gear, having taken its first fitful breaths of desert air.

I burst out into the fading Delhi afternoon to be whisked along miles and miles of motorways, flyovers and roundabouts to the bus station, and it was only after miles and miles more that anything resembling the old India appeared in the rundown avenues leading into the pink city, in the pigs rooting in the garbage, in the touts running after our bus. It was a day on The Road, and the only satisfaction I derived from it was when I crawled into bed at 2.30am at the Arya Niwas Hotel.

Day 2: The God of the road

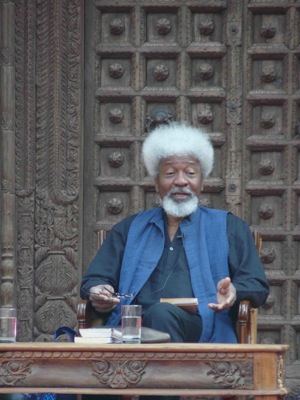

RABI THAPA Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka |

Car after car streamed through the narrow gates to disgorge shimmering visions of literati ladies exchanging kisses, handwaves, oohs and aahs, before they trooped in to throng the ornate Durbar Hall for a chance to skin their knees at a session on 'Public Conscience'. Here, Dalit writer Kancha Ilaiah chastised them for their lack of the latter, and insisted Brahmins would be better off naked to demonstrate their guilt, as Hinduism was 'a form of spiritual fascism.'

Disappointed at the focus on the rather obvious plight of Dalits rather than the positive search or even definition of what was meant by a 'public conscience', I dashed out to buy pen and paper, and was struck by the (assumed) Dalits lining the road outside the venue, waking to a new day of despair, cradling their dogs on the urine-stained walks. One couldn't help wondering.

Soyinka too had wondered, and drawn his own conclusions. At his noon reading on the Front Lawn, he chanted in a sonorous bass excerpts from his book The Road and his play Death and the King's Horseman. To Soyinka, Nigeria and India are both ruled by Ogun, the God of the Road, in as much a spiritual sense ("The road to heaven is long") as a mechanical sense ("Driver, please take care"). Soyinka himself continues to absorb and exude the essences of the road. And if he's come a long way, he had words for the road ahead that Nepal could well think on. Remarking on South Africa's process of truth and reconciliation, Soyinka cited the role of Desmond Tutu and Mandela in averting major bloodshed. But while forgiveness is all very well, he said, some people are so well versed in impunity that forgiveness will only encourage repeat offenses. Here some form of restitution, or exactment, may be necessary.

After Soyinka's considered, accessible session, the post-lunch session on 'Can the Internet save books?' fell far short of its premise. In no small part due to moderator (and TV personality) Barkha Dutt's constant interjections, antagonistic remarks and ill-informed generalisations, the debate perfectly encapsulated her own absurdly unironic lament that literature and the long narrative form were suffering because of today's 'short attention spans'.

Instead of focusing on the practical issues of a new business model that could threaten the physical format of books, as some of the panelists suggested, the debate, thanks to Dutt, dawdled around whether the Internet could threaten the quality of writing. When a man behind me demanded if the debate on social networking tools and sociopolitical change had any relevance to India outside of the rarefied air of the Jaipur fest, the chattering classes clapped on cue. By the time lyricist Javed Akhtar offered his wholly facile comment on how easily memory and knowledge would be brain-implanted in the wonderful, scary age of the Internet, I found myself following the squirrels prancing about on the big tree behind the stage. Short attention span, you might say.

Day 3: Indian queues, media scrums and Viking colonies

RABI THAPA Hanif Kureishi |

As I squeezed out into the pleasant Jaipur sun, I watched a scrum of schoolgirls and journalists jostle on the Front Lawn, and wondered absently who was in the middle of it all. After a bit, Om Puri emerged with his wife, and then Chetan Bhagat, the bestselling author whose phenomenal success with commercial novels has both the industry and the critics scratching their heads. Suffice it to say that those wanting to be close to the stars - and could you blame them? - were wholly oblivious to the miniature launch of northeastern Indian author Daisy Hasan's debut novel, 'The To-Let House'.

On the whole, however, the morning sessions were illuminating. There were more readings from the road with 'Wanderlust', comprising William Dalrymple, Geoff Dyer, Brigid Keenan and Isabel Hilton. Here travelogue as comic relief was epitomised by Geoff Dyer's recounting of his frustration with (the lack of) a queue at an Indian ATM. Dyer insists stridently on his place in the face of a placid Indian who is trying to jump the queue, secures it after much uncool blustering, triumphantly marches in, and has his card rejected by the machine. He had the audience in tears.

Hilton's measured, lyrical description of climate change in Greenland was in stark contrast as another kind of cautionary tale. Greenland was so named by Erik the Red, the Viking who landed at a relatively ice-free southern cape in 982, in the midst of what is now known to have been a 'medieval warming'. His colony died out in the late 15th century, though Inuits thrived on the rest of the icy continent. Today, the ice is thinning, and Inuits are considering cattle farming.

It wasn't all culture clash and dissolution. Come evening, Dalrymple conducted a reading to hypnotic Baul music of an India hidden enough to be exotic even to Indians. Here were impoverished Dalit workers scrabbling for a living nine months of the year and transformed into gods who possessed them come festival time. Here were Devdasis, who have sex with so-called devotees in some semblance of a divine union, falling prey to AIDS, one by one. Dalrymple goes places most adherents of India Shining care not to acknowledge.

Day 4: Reaching out to heaven

In answering this question, the Brahmanas reveal to us a worldview that is not only alien to Western philosophy, but much of modern Indian thinking itself. Calasso's work on these key texts represents an attempt to get to the "neuralgic centre of Indian thought". It's clear he believes this is key to liberate India from the tyranny of historicism and Vedic casteism, recapture lost gestures, images and concepts, and revive its legacy of spirituality.

After this perfection of articulation, it was only fitting perhaps that we snuck out into the city to traipse through the Hawa Mahal, then Jantar Mantar, the astronomical observatory built at the turn of the eighteenth century (when the city was founded). In these massive discs, triangles and half-spheres scattered across a large park-like expanse, there was surely science of the highest order (no pun intended), but they called to mind, equally, a surrealist aesthetic sensibility that meant there was no need to really understand what these medieval astronomers were actually working on. They observed the heavens; we observed the remarkable instruments they used to reach them.

Then back for another illuminating session on the late Urdu poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, whose shayaris and ghazals inspired Pakistanis lumbered by successively corrupt and tyrannical governments as the poetry of Pablo Neruda did.

And what is the role of poetry? Faiz was jailed for four years for alleged involvement in an attempted coup in 1951, and his poetry was banned. It did not stop it being sung in public, and this evening, too, we were treated to Pakistani novelist Ali Sethi's beautiful rendering of two of Faiz's ghazals. Poetry, then, for social justice. But poetry, too, for beauty. "Everything he wrote about," declared Javed Akhtar, sitting alongside Shabana Azmi, "became beautiful. Even jail."

|

Day 5 : A book or a cup of coffee?

Come Monday, the festival attendance that had started with thousands had thinned considerably. The working week for most, mental exhaustion for others, and time to prep for the IRs 5000 closing ball in the evening for yet others. Conversations with attendees indicated that five days, if stimulating, was a little too much. Perhaps it depended on who you were. Many of the mostly female students were clearly there to tot up celebrity signatures, and were not to be seen in the sessions. Writers aspiring to publication had their own agenda, beside an interest in the sessions. Published writers, reluctantly or no, had to make an appearance to market their work, and might enjoy the opportunity to interact with fellow-writers and fans. Publishers would find the festival a little more relaxed than the book fair the following week in Delhi, though still tiresome after a point. And the non-literary celebrities and literary socialites, well, the less said about them the better.

But the Diggi grounds were less overwhelming, the sessions less of a stampede for seats. In the Mughal Tent, Sri Lankan writer Romesh Gunasekara read enthusiastically from 'The Match', bringing to life a real-life cricket match between India and Sri Lanka. When Sachin Tendulkar whacks the ball, a pigeon is felled near the boundary line and the protagonist, photographing a man picking up the bird, has an epiphany. 'The bird's wings move in and out of focus," he notes, "like life itself." When the Times Literary Supplement reviewed Gunasekara's book, they printed it alongside a photo of the actual incident.

The crowds were back, however, for 'Publishing in the next decade', though panelist Shobhaa De was conspicuous in her absence. "She's probably gone shopping," sneered another panelist, and the tone continued when they began to discuss the equally famous Chetan Bhagat. "Is it even literature?" wondered one. "Do books have to be priced at Rs 95, like Chetan Bhagat's, for the Indian public to buy them?"

The discussion revolved around Tehelka's rather surprising poll on Indian reading habits. Among other revelations, the magazine found that 85% of those who bought books were male, that Indians spent a mere IRs 181 on books a month, that women read almost exclusively romance, and that Chetan Bhagat was far and away the most popular author. Disappointing perhaps for those who have invested in Indian publishing from whatever perspective. But, as Urvashi Butalia of Kali Books pointed out, this was a 'buyership' poll, not a 'readership' poll, so most of its conclusions were highly misleading. And Chetan Bhagat, as V.K. Karthika of HarperCollins said, may not be literary but writes about "being part of the world today".

There were other problems. Karthika went on to lament the lack of effort by retailers to promote mid-list books without awards or celebrity authors to push them. When Ravi Singh of Penguin India noted that Indians were as likely to buy a cup of coffee as buy even the cheapest of books for Rs 95, Karthika insisted the reading public, too, had to be willing to pay more for intellectual property. And this property had to be valued appropriately. If cronyism meant a true critical culture was suppressed, then what would this mean for the reading culture?

The good news, they all agreed, was the proliferation of small publishers - Chennai's Blaft, Delhi's Narayana, and Yoda Press. This was where the change was happening. But the picture they painted was sobering. How would this reflect on Nepal, where most publishers are little more than retailing houses with little respect for intellectual property?

There's one way to test the waters. Watch out for the Kathmandu Literature Festival, 2011.

READ ALSO:

Envy thy neighbour - FROM ISSUE #487 (29 JAN 2010 - 04 FEB 2010)