At night, when the district capital of Simkot is in darkness, across the valley the village of Langduk is all lit up.

At night, when the district capital of Simkot is in darkness, across the valley the village of Langduk is all lit up.

Children do their homework under fluorescent lamps and their parents watch tv from a cable network. The contrast between Langduk and Simkot is emblematic of the hope and despair in this remote district on the northwestern tip of Nepal.

Simkot is still dark because a 500 kilowatt powerplant on the Hildung River lies half complete and abandoned. Despite having a minister in the last royal regime, Humla's voice is too feeble to be heeded in faraway Kathmandu.

Langduk's residents, on the other hand, never expected much from the government and prospered through sheer hard work. Ten years ago a Canadian charity helped farmers here set up greenhouses and today each of its 14 households earns up to Rs 75,000 a year selling vegetables through a cooperative in Simkot. Langduk set aside its own community forest and is now putting up a herbal farm. At the Mahakali Primary School, enrollment is 100 percent and eight of the 17 students are girls (picture, above). Teacher Binod Shah is worried about having fewer students but it's a sign that rising living standards and literacy have brought down the birth rate.

The villagers recently installed their own hydropower plant and an improved watermill. Langduk's cooperative charges Rs 5 per light bulb per month, Rs 10 for a colour tv and now has enough saved up to increase generation capacity.  If the rest of Nepal was as committed as Langduk, this country would already have met the UN's Millenium Development Goal of halving poverty and improving nutrition and literacy by 2015. How did they do it?

If the rest of Nepal was as committed as Langduk, this country would already have met the UN's Millenium Development Goal of halving poverty and improving nutrition and literacy by 2015. How did they do it?

"Others try to do big things," explains Gobinda Lama, the soft-spoken secretary of the cooperative, "but we started small and learnt as we went along." In ten years a village that depended on selling firewood is conserving forests and prospered by switching to selling vegetables.

Sita Lama helped Langduk ten years ago with vegetable farming when she was with USC-Canada. "We worked as hard in other villages too but here people were very conscientious and there was a tremendous willingness to learn and work hard," she recalls.

There was similar enthusiasm across Nepal in the mid-1990s with the Local Self-Governance Act and the election of VDC and DDC councils. Elected grassroots leaders had to be accountable and were judged on performance. Jivan Shahi was Humla's elected DDC chairman till Sher Bahadur Deuba dissolved all local bodies in 2002, and says: "We were convinced Humla's development was linked to road access but we didn't just sit around talking about it, we started digging."

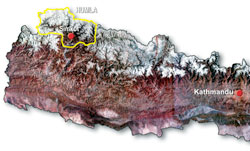

Shahi's priority was to build the 80 km highway linking Simkot to the Chinese border so the cost of food and basic needs could be reduced and provide access to markets for Humla's fruits and herbs.

Under a WFP food-for-work program, 35 km from Hilsa to Yari was completed but work is now stuck because there is no money for bridges and to cut through rock faces.  "If we have the money we can finish this road in two years and that will transform Humla," says local politician Tsiring Utup Lama, "it will be our spinal chord."

"If we have the money we can finish this road in two years and that will transform Humla," says local politician Tsiring Utup Lama, "it will be our spinal chord."

The DDC's other priority areas were health, sanitation, education and food sufficiency. Lack of arable land in this rugged and arid region means that Humla's 45,000 people only grow enough food to feed themselves for three months a year. For the rest, they migrate to work or depend on 100 tons of rice a year that has to be flown in from Nepalganj at a cost of Rs 60 million.

If only a part of that amount could be invested in irrigating some 1,500 hectares of rainfed farms along the Karnali in southern Humla it would boost food production permanently. This year's winter drought has made things much worse right across western Nepal. Says Shahi: "We have to phase out food subsidies and phase in irrigation so we don't have to forever depend on expensive airlifted drops."

No matter who the rulers are in Kathmandu, Humla has always been passed over. Now that democracy has been restored there is a chance that the good start made in the mid 1990s with decentralised political power can resume.

At a meeting of political parties, NGOs and others in Simkot last week, economist Chaitanya Mishra summed it all up amidst applause: "It is now up to elected local leaders to connect politics with development again."

Humla lite

Humla lite

Most of us take the electric light for granted but one has to be a Humli to really value it. The people of this trans-Himalayan region can't afford kerosene and have traditionally burnt sooty pine pulp for domestic lighting.

But smoke from these lights and kitchen fires means Humla and adjoining districts have the highest infant mortality rate in Nepal because of acute respiratory infections.

Now, a unique project that aims to get a Nepali family with electricity to give electricity to a Nepali family without it is bringing a neon glow into the interior of homes in Humla. Nearly 400 Nepalis have donated Rs 4,000 for the scheme which aims to install solar-powered battery systems in 500 homes here. Dalit and poor families have been the first to get the lights and are ecstatic.

"Our eyes don't itch, the children don't cough anymore and can do their homework at night, our clothes aren't black, and I can work on my stitching machine at night," says Kanna Damai.

For another Dalit, Gore Sunwar, it was an emotional moment to finally meet the man who made all this possible: journalist Bhairab Risal. "You are the only one who thought of us poor people, no one else has," Sunuwar told Risal, "my children are in school and they aren't sick anymore."

At 77, Risal is still tirelessly pursing his project and is already looking at replicating Humla's success in Mugu and Jumla. Moscow-based Nepali Jugal Bhurtel has donated Rs 200,000 for 50 lights and the diaspora group, Help Nepal is funding 100. "Raising money is the easy part," says Risal, "the hard part is the logistics and making sure there is training and backup."

Donations pay for the cost of the panel, two 6 watt lamps and a battery while a government subsidy takes care of transportation. Households have to pay Rs 1,500 for the installation.

For Kanna Damai it's all worth it: "Inside the house it is now brighter at night than during the daytime."

Humla Ma Ujyalo: 977-1-4232052

Bad blood An interaction program between local representatives of the political parties and the Maoists recently in Simkot showed just how difficult it will be, despite the ceasefire, for things to get back to normal.

An interaction program between local representatives of the political parties and the Maoists recently in Simkot showed just how difficult it will be, despite the ceasefire, for things to get back to normal.

Humla's internally displaced families demanded a return of confiscated property and guarantees that they can return safely to their homes and farms. When the Maoists said the returning families would have to abide by their rules, the IDPs heckled them.

"I don't know why I was displaced, and I don't know why I can't go back," said 77-year-old Kanna Shahi (pictured) whose property was confiscated and then severely beaten up by Maoists last year. A Simkot resident's daughter and son joined the Maoists, but this didn't protect his house from being destroyed by Maoists for having joined the DDC.

Indeed, local rebels haven't done much to instill confidence. They are extorting 'tax' from every shop in the bajar and are demanding a month's pay from all civil servants here. Last week a Maoist got inside Simkot airport and forced Indian pilgrims returning from Mansarobar to cough up Rs 35,000.

There are signs of normalcy: Maoists have opened an office in the town and district chief Comrade Askar met with the CDO and chief of police and army last week and assured them of his party's intention to follow the 12-point agreement. When asked about IDPs, he replied: "If they want to go back, we can return them their property."

On Tuesday they held a mass meeting on the only piece of flat ground in Simkot-the airfield. There were revolutionary speeches, songs and dances and following the practice elsewhere, hundreds of people were marched in from surrounding villages.

But given the bad blood, it is doubtful if in Humla the Maoists can win back the hearts and minds of people with just slogans and music. Many are too scared to go back to their villages and others have nothing to go back to because their houses have been burnt down, their farms confiscated and their livestock and possessions looted.

People here still remember the brutal slaying of Tsiring Jangbu, a 65-year-old woman from Bargau two years ago who was beaten to death when she tried to obtain the release of her daughter who had been forcibly recruited by the Maoists. Or Ram Prasad Bhusal, a popular teacher in Buruse who was abducted, forced to dig his own grave and killed two days later for being a Nepali Congress supporter.