Ram Sharan Mahat's book, In Defence of Democracy: Dynamics and Fault Lines of Nepal's Political Economy, due to be released on Tuesday, ends up being a post-mortem of our adolescent democracy. The 1990 People's Movement brought unprecedented political and economic freedom to Nepalis, but democracy died young. This book is Mahat's attempt to figure out what went wrong, what went right, and an effort to trace the structural stresses that contributed to the country's present state.

Ram Sharan Mahat's book, In Defence of Democracy: Dynamics and Fault Lines of Nepal's Political Economy, due to be released on Tuesday, ends up being a post-mortem of our adolescent democracy. The 1990 People's Movement brought unprecedented political and economic freedom to Nepalis, but democracy died young. This book is Mahat's attempt to figure out what went wrong, what went right, and an effort to trace the structural stresses that contributed to the country's present state.

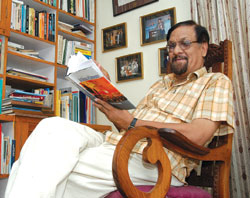

Mahat gave up a promising career in the UN system to return home after 1990, was appointed to the National Planning Commission, contested elections from his native Nuwakot and became a NC member of parliament to serve as Finance and Foreign Minister. Mahat witnessed the heady euphoria of democracy, the subsequent disillusionment with it, and its eventual dismemberment by the Maoists and a reassertive king.

The creeping coup that started with the royal move on October 2002 was justified on grounds that political parties had made a mess of things with their incessant bickering and corruption. It was further argued that these shortcomings contributed to the rise of the Maoist revolution and its rapid spread. If asked, most Nepalis would agree.

But despite disenchantment with the shenanigans of politicians, Nepalis still overwhelmingly favour parliamentary democracy. The reason may be that although politicians in Kathmandu may have let the people down, there was a groundswell of demand for services from elected local councils. Rural Nepal was being transformed by this empowerment.

In his book, Mahat backs this up with figures. The road network more than doubled between 1990 and 2002, the proportion of Nepalis with access to electricity went up from nine percent to 40 percent, and those with access to safe drinking water nearly doubled. The average life expectancy of Nepalis rose six years to 59 within a decade.

As Finance Minister, Mahat was entrusted with the job of budget allocations and had his priorities. Not everyone agreed with those priorities, and as a politician he had to make compromises. But post-1990 economic reform and political decentralisation had created the environment for progress, allowing Mahat and his colleagues to lay the foundations for achievements in community forestry, media and communications, privatisation and deregulation, trade and exports, hydropower, foreign investment and sustained economic growth.

As Finance Minister, Mahat was entrusted with the job of budget allocations and had his priorities. Not everyone agreed with those priorities, and as a politician he had to make compromises. But post-1990 economic reform and political decentralisation had created the environment for progress, allowing Mahat and his colleagues to lay the foundations for achievements in community forestry, media and communications, privatisation and deregulation, trade and exports, hydropower, foreign investment and sustained economic growth.

In In Defence of Democracy Mahat sounds defensive, and the reason is that there is such a concerted offensive now to uproot democracy. The ex-minister gives us a peek behind the scenes at the struggle to craft policy reforms necessary to make change happen. And all this becomes terribly relevant post-February First as the nation is being dragged back not just to pre-1990 but pre-1960.

Any Nepali who says Nepalis aren't ready for democracy is insulting himself. We were not only ready for democracy, we thrived under it. Yes, we could have done a lot better if the politicians had been less venal. But dictatorship was worse: just look back at the 1960-1990 period, the two and half centuries before that, or post-October 2002.

Mahat admits that the political failures of successive elected governments to respond to the national needs may have contributed to the rise of Maoism, but argues that much more of a factor was the entrenched feudalism and the traditional disregard of Kathmandu for the rest of the country. He admits: 'Democracy is essential, but not necessarily the sufficient condition to prevent a sense of injustice and exclusion of marginalised groups.'

But after 1990 power was transferred from Kathmandu's oligarchs to a new breed of rural middleclass Nepalis. Many of them turned out to be hill bahuns, so what we saw was parliament, politics and the bureaucracy more bahun-chhetri dominated since 1990 than ever before.

Mahat devotes an entire chapter to rake up Arun III and thinks its cancellation was a 'national loss'. Although he himself flipflopped on Arun, in the book he is bitter about activists who opposed it, the donors who dumped it and the UML government which played politics with it. Ten years after the $1 billion project was cancelled, he is convinced the two Aruns would have delivered the cheapest firm energy. What Mahat doesn't point out is that in place of Arun III we have dozens of smaller plants that generate nearly twice the energy built in half the time for less than half the cost of that mammoth project.

Subsequent chapters are on corruption (graft in Nepal was blown out of proportion by a newly-free press), the Bhutani refugee crisis (Nepal shouldn't agree on assimilation), a recap of the Maoist war right down to February First (the king has played into the Maoists' hands by polarising the political forces against the monarchy). The last chapter goes into the 'fault lines': the stresses in the polity that led to democratic decay, disparities and centralisation, the crisis in education, deepening donor dependence.

Yet, as Kul Chandra Gautam of UNICEF argues in the foreward, 'democracy tends to be a self-correcting system, and given a fair chance the distortions can and will have been rectified'. Given time, Mahat is convinced we would have got there.

Unfortunately, the people couldn't wait. And as it turned out, neither would an ambitious king.

In Defence of Democracy: Dynamics and Fault Lines of Nepal's Political Economy

by Ram Sharan Mahat, PhD

Adriot Publishers, New Delhi, 2005