It's not yet dawn here in Ramechhap district but we are awakened by a 'tung tung' sound from down the road.

It's not yet dawn here in Ramechhap district but we are awakened by a 'tung tung' sound from down the road. The village of Shivalaya is on the east bank of the Khimti Khola and it is still dark outside. Gradually, we can make out the inky silhouette of the mountains as the eastern sky slowly lightens up.

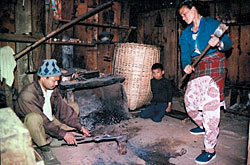

We follow the sound and come up to Ram Lal Biswokarma's workshop. Three members of his family have been up since four in the morning to fire up the furnace and pump the bellows. Ram Lal pulls out a red hot slice of steel from the roaring fire with his tongs and places it on the anvil. (See picture) His wife, Chameli, strikes it with her hammer block with all her might. Sparks fly. Once, twice, thrice until the red glow turns to ash pink.

Kanchha, their eight-year-old son, is also awake and watches his parents forge another khukuri. In the grip of conflict, it is rare to see anyone working at night anymore in the village. But Ram Lal needs to finish six khukuris in time to take it to the market in Those or in Jiri and with the money buy a school uniform and stationery for Kanchha who is starting primary school in the new year.

Despite the noise from his workshop, no one in Shivalaya complains about it. Everyone knows how much the Biswokarmas have to struggle to make ends meet in these difficult times.

The family is not from Shivalaya. A month ago they finally fled their home village of Alung. Ram Lal still has a home and fields there. But the security forces broke into his house one night two months ago and accused him of supplying khukuris to the Maoists. They destroyed his furnace and scattered his tools and went away.

"I don't even know what a Maoist looks like, if I saw them I wouldn't be able to tell them apart from the soldiers," says Ram Lal, "but they wouldn't listen. We decided to leave our home."

It's now eight, the sun has crested the hill, porters are making their way past Ram Lal's shop across the bridge and up the steep trail with their mules and yaks.

But the Biswokarma family is still busy trying to finish the khukuris. Ram Lal says it will take another hour to sharpen the edges of the new khukuris. He has no time to engage in small talk with reporters.

Kanchha says shyly that he misses his home in Alung, "I have no friends to play with here." We go outside to the next door teashop where some customers are sitting talking in murmurs in the smoky kitchen. At the sight of an outsider, everyone stops talking. This is the big change in Nepal: garrulous teashop banter replaced by this unnatural silence.

Rasmila Shrestha, 15, runs the family teashop but won't be doing so for much longer. She is finding it more and more difficult to live in Shivalaya. She stopped going to high school last year after news spread that the Maoists were forcing children to join their 'people's war'. "I am saving for the bus fare," Rasmila tell us quietly, "I'll go and get enrolled in Kathmandu, there is nothing for me here any longer."

From Ram Lal's house, the whining sound of sharpening knives suddenly stops. The khukuris are ready.

hancha is so excited about accompanying his father to the Jiri market that he has already eaten. Chameli serves her husband dal bhat and he eats quickly. The little boy can't contain his happiness. As he walks up the mountain ahead of his father, Kanchha shouts back at us, "I'm getting a new uniform today."

Some names have been changed to protect the family's identity.