Harivansh Rai Bachchan came from a Kayasth family, whose origins revert three centuries back to the village of Amroha in Basti district of one-time Awadh. This became the United Provinces of Agra and Avadh under the British, the Uttar Pradesh of modern India. Harivansh's autobiography, In the Afternoon of Time (translated from original Hindi by Rupert Snell, Penguin India, 2001), provides an opportunity to understand a disappeared period and lifestyle that is part of the common Southasian experience of the Ganga plains.

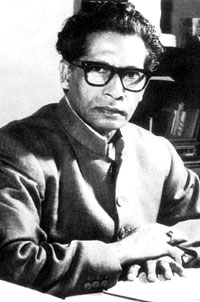

Harivansh Rai Bachchan came from a Kayasth family, whose origins revert three centuries back to the village of Amroha in Basti district of one-time Awadh. This became the United Provinces of Agra and Avadh under the British, the Uttar Pradesh of modern India. Harivansh's autobiography, In the Afternoon of Time (translated from original Hindi by Rupert Snell, Penguin India, 2001), provides an opportunity to understand a disappeared period and lifestyle that is part of the common Southasian experience of the Ganga plains. 'Bachchan' was what he was called in the family, meaning 'child' or 'boy', and the poet Harivansh retained it as his nom-de-plume. It is the surname that the elder son Amitabh made famous through his Bollywood mega-stardom. Harivansh's youth spanned a time before and after the First World War, the years of on-again off-again revolt against the British, with MK Gandhi seeking to calibrate the revolt to stay within the ambit of peaceful satyagraha.

When the poet was growing up in Allahabad, forsaking Urdu study for Hindi which was in the process gaining supremacy, the differentiations between Braj Bhasa, Maithili, Bhojpuri and other vernaculars of the Ganga maidaan were still considered significant. There was more fluidity back then across sectarian and religious boundaries. This being Prayag, where the two great rivers meet, the men bathed in the Ganga and the women in the Jamuna. The women worshipped Bhavani, while the males gravitated towards a Shiva temple built by an ancestor. Krishna's birthday, Janmastami, was celebrated, as was Muharram.

Amidst visits by hakims, vaidyas and homeopaths to the family home, Harivansh's childhood and youth includes a long and continuous list of family members breathing their last. The killers were consumption (tuberculosis), measles, malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia, seizures, various infections, and childbirth complications. In Harivansh's recounting, there are always new orphans, widows and widowers in the mohalla, and deities being propitiated to keep the grim reaper at bay.

Four babies had died before Pratap Narayan and Sursati gave birth to Harivansh. His nanny, who feeds Harivansh mother's milk after her own infant dies, passes away when the poet is still a child. His closest playmate, a cousin named Patto, is suddenly is taken ill and never seen again. "I overheard the grown ups saying that Patto had died and all sorts of questions came up in my mind. Do children die? What does it mean, this dying? Does a child turn into a kind of vapour and vanish into thin air?"

Young Harivansh sees death for the first time when his sister Bhagwandei passes away, lying in a charpoy in the household courtyard. Two months later an aunt named Maharani is gone, none the stronger for being proud and unbowed against familial intrigue. Within a month, her mother Radha dies at age 95, carrying with her the family history harking back to the ancestors of Amroha. Then Maharani's daughter Buddhi breathes her last, alone in a hospice after having been sent away so as not to disturb the wedding of a cousin.

"Deaths were taking place so thick and fast.. That we began wondering anxiously how long the sequence would go on and whose turn it would be next." Before long, an elder cousin's wife passes away, giving birth to a stillborn child. "Six deaths in less than a year would be enough to shake any family and I began to feel a strange emptiness within me.The last year's spate of deaths seemed to leave many spaces empty around me, many links in the chain of relationships broken."

Beyond the family, Harivansh's close friend Karkal gets drenched in a downpour and dies of high fever. His ashes are borne away by the Ganga, and before long his wife and Harivansh's confidante Champa's ashes too follow. But the sharpest blow is meted out over the years as the poet's wife Shyama struggles against intestinal tuberculosis. She teeters between life and death for eight years before departing, leaving behind a distraught Harivansh.

Among the upper and lower middle classes of Southasia, this persistent visitations of death is now a matter of history. Simply put, there are fewer members in families and fewer deaths, particularly among children and young adults. But as is clear from this evocative autobiography, back then people passed away in the home surrounded by a circle of concerned family members. Today, the Southasian middle class dies more often than not in dilapidated hospital wards reeking of disinfectant, removed from relations and friends. That, too, is evolution.