I felt sorry for myself when, imagining some non-existent reason to get back to Kathmandu, I rushed down from Bupsa and twisted my ankle.

I felt sorry for myself when, imagining some non-existent reason to get back to Kathmandu, I rushed down from Bupsa and twisted my ankle.

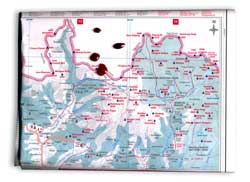

Hobbling along, I really wanted to know just how long it would take for me to get to the warm lodge at Nuntala. I pushed through Jubing and crossed the bridge by noon, stopping to iodise my water and check the time so I would know when I could drink it. I climbed up to the small teahouses past the bridge and thought, surely it could be no more then two hours up the hill. I looked at my watch: 15 minutes till I could drink.

As I sat, a dozen soldiers appeared in the scrub at the far end of the small hamlet, with them two Nepali teenagers, a girl and a boy. They seemed to be arguing. The soldiers gestured at them with waves of their M-16s. The two were now hysterical, shouting back at the soldiers.

I looked at my watch, 13 minutes. When I looked up again, the two teenagers were running away from the soldiers, heads down and running hard towards where the plateau that the village stood on dropped to the river and the bridge. A couple of soldiers raised their weapons and almost casually fired five, six rounds. A short burst, and they both fell, one attempting to rise and failing. Two more soldiers walked over and one kicked them, hard, before bending with a pistol and making the dying youths almost sit up with the force of the coup de grace to the head.

I looked again at my watch, registering the fact that I had wet myself. Eleven minutes. The soldiers had seen me and as they prepared to leave, one of them walked over to me, hanging his head shyly like a guilty schoolboy. He stood in front of me trying to summon up some English, finally settling on "bad people" before joining the rest of the platoon heading up to Khari Khola.

That night I asked Raju in Nuntala for a jug of chang. But after one sip, I was retching in the street, unable to stop shaking. I went to my bed, where I could not sleep.

The next day, coffee, breakfast and the climb to Takshindo. The hills were full of army, their cordon moving across the hillside, clearing out Maoists, the occasional burst of gunfire drifting across the hillside as I plodded up. At the Everest View, buying cheese and dried apples, a deaf-mute woman in her sixties mouthed at me, miming shooting. She pulled her skirt up to show a horrific khukri slash, half healed. The lodgekeeper told me Maoists had done it.

The day and light were ending, and clouds were blowing up from the valley across the hill, parting over Takshindo. The lodgekeeper pointed out Thamserku and Kangtega. Why had it been so important for me to know which ones they were?

The lodge in Junbesi was warm and welcoming, the dining room sunny, as the Rai kitchenboy fried eggs. The sauni chatted to me about the Kathmandu schools her children attended. In the last 24 hours, I had turned into a complete chatterbox. Children, trekkers, shopkeepers. I seemed to need the sound of my own voice to confirm my existence.

The sauni's husband was keen to tell me how the army was in the woods above, between me and the Lamjura, chasing Maoists. I tried to ignore him, but as he talked I had to listen. When they caught Maoists, he told me, they tell them to go, to run away, and then they shoot them down. Villagers know not to run, to stay put and they will not shoot you. Then they know you are just gathering wood. I remembered the boy and the girl. But how do they know they are Maoists, I ask. He looked at me like I was stupid. "Because they run away."

A day in the hills of Nepal is a life.a simple, trite, much used phrase. When you trek through these places you are lucky that from the morning peppery chia to the evening dal bhat, you are privileged to see a whole lifetime. You will become part of a landscape in motion as you move through ever-changing mountain views to the changing emotions that play across the faces of children. It will change your life as it has mine. But as I found, and continue finding, it could not be relegated to a corner of your life.

So how far is it to Nuntala? It is the time it takes for ama to serve out a helping of yogurt and refuse payment. It is the time it takes Tashi in Kyangjuma to see our meal is perfect despite the huge trekking group we share her lodge with, and the fact that armed Maoists robbed her lodge last night. It is the time it takes to spend with a friend, it is the time it takes to realise the soldiers are as frightened as you are, and if you run, they will shoot. It is the time it takes to realise a remark is thoughtless and wish it unsaid. It is the time it takes to play with and talk to children rather then just photograph them and pass on. It is the time it takes to realise how short life is.

It is the time it takes to realise every moment is important and we can make a difference, both in our own lives and in the lives of those we meet along the way. Ask me anything but please not how far it is or how long it will take, because when you know that, you will also know that it will end.

Alden Pyle is the pseudonym of a trekker who travelled across the Junbesi valley earlier this year and witnessed the events described.