We're used to it, but the first thing visitors to downtown Kathmandu remark on is that vast, conspicuous swathe of open space called Tundikhel. For a city that has seen such extensive documentation of its buildings and spaces in the last three decades, there are surprisingly few people-government functionaries or independent researchers-who know anything about Tundikhel's history or its social significance. Everyone knows that there was a massive tented camp here after the 1934 earthquake, but few people understand why it is the spot of so many military parades, and no one can even tell you how many square metres it covers. Now, the nine ft-high fences being erected around Tundikhel might mean even less interest in a part of Kathmandu as steeped in legend as any Darbar Square.

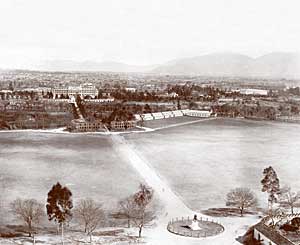

We're used to it, but the first thing visitors to downtown Kathmandu remark on is that vast, conspicuous swathe of open space called Tundikhel. For a city that has seen such extensive documentation of its buildings and spaces in the last three decades, there are surprisingly few people-government functionaries or independent researchers-who know anything about Tundikhel's history or its social significance. Everyone knows that there was a massive tented camp here after the 1934 earthquake, but few people understand why it is the spot of so many military parades, and no one can even tell you how many square metres it covers. Now, the nine ft-high fences being erected around Tundikhel might mean even less interest in a part of Kathmandu as steeped in legend as any Darbar Square. Henry Ambrose Oldfield, British resident surgeon in Kathmandu, wrote in his 1850s book Sketches of Nepal that Tundikhel originally spread from where Rani Pokhari is today in the north to where the Dasarath Stadium is in the south. He estimated that it measured two-three miles in length and about 300 yards in width, making it one of the Asia's biggest parade grounds at that time.

Since Tundikhel lies in the heart of the city, it has always mattered to those who would make their authority felt. Way back in 1671, King Pratap Rana made the first incursion into this space when he directed that Rani Pokhari be built to console his queen.

But the first mention of Tundikhel by name was later, in 1709, in a scripture engraved in the Taleju Bhagawati temple by Queen Bhuvan Laxmi. During the Malla period, Tundikhel was a vast open space maintained by the rulers for social and cultural events, including Ghode Jatra celebrations. Some researchers argue that Tundikhel was an architectural requirement of the Malla era-vast open spaces were considered essential near any densely populated settlement. As the rest of the Valley expanded to accommodate new, wealthy towns, darbars

and shrines, Tundikhel alone remained open.

It still is, although over the past 150 years, the demands of modernisation, and the need to legitimise Rana rule slowly constricted it from all sides. "Encroachment of Tundikhel started when the rulers started garnering military power. They overlooked its social and cultural significance and made it out of reach of the communities in order to use it to their own benefit," explains Bal Dev Juju, an expert on Newar culture.

It still is, although over the past 150 years, the demands of modernisation, and the need to legitimise Rana rule slowly constricted it from all sides. "Encroachment of Tundikhel started when the rulers started garnering military power. They overlooked its social and cultural significance and made it out of reach of the communities in order to use it to their own benefit," explains Bal Dev Juju, an expert on Newar culture. Until Jang Bahadur Rana came to power, the army was trained and paraded in the Chhauni grounds. Bhimsen Thapa might not have envisioned developing Tundikhel as a military parade ground but his decision to build a palace for himself in Lagan Tol, south-west of Tundikhel, in 1813/14 brought soldiers closer to Tundikhel. Barracks were constructed on the east and north sides of Tundikhel, where the Karmachari Sanchaya Kosh's main office now stands, and a foundry was built to manufacture cannons on the south-western side.

Juju says that Ghode Jatra was at one time only symbolic-the horse of the Kathmandu Kumari would be let loose at Tundikhel during Indra Jatra. But when Jang Bahadur returned from England, he realised that the festival had the potential to show off his military strength even as it entertained foreign visitors. Tundikhel was turned into a parade ground for the Nepali army as early as the mid-1830s, towards the end of Bhimsen Thapa's premiership, and Jang Bahadur reinforced this new use of the space, but it was Bir Sumshere, who proclaimed himself prime minister following a coup in 1885, who turned Tundikhel fully over to military use.

At the centre of Tundikhel was the Khari ko bot with a marble platform around it, under which the Rana rulers made all significant announcements-Jang Bahadur summoned the army to challenge King Rajendra in 1848, Bir Sumshere proclaimed himself prime minister at that spot in 1885, Chandra Sumshere announced the emancipation of slaves in 1924 in the same place, and finally, the Allies' success against Hitler's Germany was announced and celebrated here in 1945.

The political significance of Tundikhel started declining after the end of the Rana regime in 1951, but then the encroachment began, and was institutionalised during the Panchayat years. Says historian Rajesh Gautam: "Tundikhel started shrinking faster even as the world was realising the significance of open spaces and got serious about preserving historical and culturally important spaces."

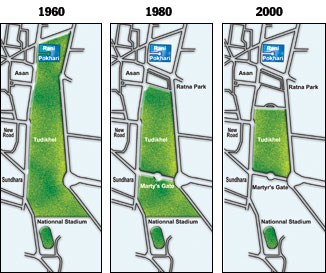

In 1961/62, the US government helped support a food-for-work programme which was used to divide Tundikhel into three separate parts and fence them off. Ratna Park and Dasarath Stadium were built, squeezing in Tundikhel from the north and south sides, and so was Shahid Gate, which was constructed without any consultation with the communities that lived around the area. More recently, the Royal Nepal Army built an officer's mess against public opinion and until late 1992, the space adjoining the Khulla Manch was allocated for a flea market.

In 1961/62, the US government helped support a food-for-work programme which was used to divide Tundikhel into three separate parts and fence them off. Ratna Park and Dasarath Stadium were built, squeezing in Tundikhel from the north and south sides, and so was Shahid Gate, which was constructed without any consultation with the communities that lived around the area. More recently, the Royal Nepal Army built an officer's mess against public opinion and until late 1992, the space adjoining the Khulla Manch was allocated for a flea market. The latest onslaught on this defining feature of the capital has been its fencing off by the Department of Urban Development and Building Construction (DUDBC). Gautam for one is unhappy about this, as are many members of the general public. "Tundikhel is our history, everyone should have access to the ground," he says.

But people like environment campaigner and tourism entrepreneur Bharat Basnet, who started a clean-up campaign in Tundikhel ("Citizen Bharat", #92), believes the move will help stop encroachment and misuse of the space without restricting the cultural activities that take place here, or the access of the public to it. Ravi Shah, site engineer for the fencing project, recalls how crucial Tundikhel was after the 1934 quake, and says: "The fencing is to prevent encroachment. We want to preserve the open space and make it useful during calamities."

The DUDBC plans to fence Tundikhel in three phases at an estimated cost of Rs 28.1 million. The department estimates that the space will be able to accommodate 300 tents during large-scale emergencies. Five emergency gates will be built for large scale movement of people to Tundikhel, but the gate through which the public now enters will retain its present function. Explains Amrit Shresthcharya, senior divisional planner at the DUDBC, "Kathmandu's open space is being encroached on mainly due to wrong policies. With planning and execution of the kind we are undertaking here, we will be able to prevent further encroachment in Tundikhel."