One cool October morning this year, eight of us rented a Toyota SUV and headed off on the Arniko Highway for Zhangmu. Known in Nepali as Khasa, the border town is 124 km away. It took Newari artisan Arniko himself much longer to make this journey in the 13th century, when he went to China building pagodas along the way.

One cool October morning this year, eight of us rented a Toyota SUV and headed off on the Arniko Highway for Zhangmu. Known in Nepali as Khasa, the border town is 124 km away. It took Newari artisan Arniko himself much longer to make this journey in the 13th century, when he went to China building pagodas along the way. Shortly after noon, we arrived at Tatopani on the Nepali side where we went through the formalities of obtaining an official document from the Nepali customs and immigration department. Although normally you must have a passport with Chinese visa to enter the Tibetan Autonomous Region, the governments of China and Nepal have agreed to allow people living within 30 km on either side of the border to travel back and forth with only an official \'chit' from a government official. Ostensibly, this is to allow traders to continue their traditional barter economy.

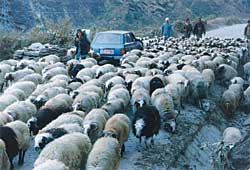

At Tatopani, as we crossed the Friendship Bridge into Liping in Tibet, we could already see tall concrete buildings glittering in the sun along Zhangmu's ridgeline. Looking back toward Tatopani and Nepal, all we saw were a few huts and shops, and naked hills, a none-too-subtle image of impoverishment and underdevelopment. For the 15-km stretch to Liping, we got a taxi, our progress considerably slowed by trucks laden with goods heading to Kathmandu along the narrow, winding, rather dilapidated road.

Awaiting our turn at the Chinese immigration post in Zhangmu, we tried not to look nervous. We'd been warned by friends that if any of us were denied entry, we should quietly "disappear"-and rejoin the line an hour later. Some people tried three times in the same day before they were let in. One of us, Sampurna, was stopped and asked to step aside by a rather angry Chinese official who, shortly thereafter and without further ado, asked him to go right on. Rather than sit around contemplating the supposedly mercurial nature of the border guards, we scurried in before the official could change his mind again.

Awaiting our turn at the Chinese immigration post in Zhangmu, we tried not to look nervous. We'd been warned by friends that if any of us were denied entry, we should quietly "disappear"-and rejoin the line an hour later. Some people tried three times in the same day before they were let in. One of us, Sampurna, was stopped and asked to step aside by a rather angry Chinese official who, shortly thereafter and without further ado, asked him to go right on. Rather than sit around contemplating the supposedly mercurial nature of the border guards, we scurried in before the official could change his mind again. We had been told to return to Nepal by 5PM Nepali time, which meant we only had three hours to get back. But in Tibet, which runs to Beijing time, it was already six in the evening! Our Nepali merchant friends then told us the Chinese didn't really mind if people like us stayed the night in Zhangmu.

We got two rooms in one of China's ubiquitous and sometimes misnamed Friendship Lodges, again recommended by friends, because it was run by a Nepali-speaking Tibetan woman. Each of us paid Rs 80 for the rooms and use of the common bath. Happily, we discovered that Nepali currency is accepted everywhere in Zhangmu because the Tibetan and Chinese traders use it to buy noodles, butter, flour and other goods from Nepal.

Shops, banks, impressive office buildings line the 1 km-long paved road that snakes through downtown Zhangmu. Strangely enough, Chinese taxi drivers are legion. Who, I wondered, hires them to go down such a short strip. Around a small town like this in Nepal there would be terraced fields of corn or paddy, but the \'crop' surrounding Zhangmu are tall concrete structures. The architecture of these buildings is such that you immediately think you're in a miniature Chinese city, instead of Tibet.

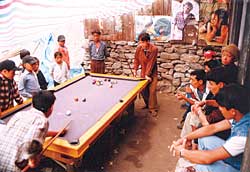

Shops, banks, impressive office buildings line the 1 km-long paved road that snakes through downtown Zhangmu. Strangely enough, Chinese taxi drivers are legion. Who, I wondered, hires them to go down such a short strip. Around a small town like this in Nepal there would be terraced fields of corn or paddy, but the \'crop' surrounding Zhangmu are tall concrete structures. The architecture of these buildings is such that you immediately think you're in a miniature Chinese city, instead of Tibet. For the past 12 years, Zhangmu has been the central exit point for Chinese goods entering Nepal. The town was full of Nepalis buying and selling, eating in restaurants, unloading trucks and strolling about chatting and laughing with their Chinese counterparts. Many Chinese spoke a smattering of Nepali, and Nepalis spoke broken Mandarin. But what impressed-and puzzled-us was the predominance of young and beautiful Chinese girls, all fashionably dressed in short skirts and tight T-shirts, with the most up-to-date hairdos. All of us, the men in particular, thought the slim and slick women looked like ramp models, but we also wondered how and why such visions of loveliness had landed in this remote outpost of civilisation. We would soon realise that there was much more to Zhangmu than just "Khasa".

With time on our hands, we rested a while and then freshened up to look our best for a night out. Stepping out was a revelation. The good citizens of Zhangmu were bustling about with renewed vigour and purpose. Once again, we were attracted-as, apparently, was every male in town-to the women we had christened the Angels of Zhangmu. It was a surreal scene. Inside the numerous beauty parlours, they were putting on make-up and getting their hair done. There were more women on the streets, some with stylish hats on, others clutching cigarettes as if they were oxygen masks on a turbulent flight. Had we stumbled onto the annual carnival? From the windows of the buildings lining the street, we saw more lovely ladies gazing down at the pedestrians. Looking carefully, we concluded that these were not the wives, daughters or daughters-in-law of those homes. Past the women, through the windows, we saw walls adorned with posters of naked women.

With time on our hands, we rested a while and then freshened up to look our best for a night out. Stepping out was a revelation. The good citizens of Zhangmu were bustling about with renewed vigour and purpose. Once again, we were attracted-as, apparently, was every male in town-to the women we had christened the Angels of Zhangmu. It was a surreal scene. Inside the numerous beauty parlours, they were putting on make-up and getting their hair done. There were more women on the streets, some with stylish hats on, others clutching cigarettes as if they were oxygen masks on a turbulent flight. Had we stumbled onto the annual carnival? From the windows of the buildings lining the street, we saw more lovely ladies gazing down at the pedestrians. Looking carefully, we concluded that these were not the wives, daughters or daughters-in-law of those homes. Past the women, through the windows, we saw walls adorned with posters of naked women. At the street-level shopfronts, we saw groups of women chatting and knitting, and we wondered why they would knit sweaters standing at the entrance rather than inside in their rooms. Our little promenade reached the end of the paved street, which was also the end of the town. It had become dark and we turned around, and on the way back noticed that at the entrances where women were standing, apparently engaged in the rather domestic activity of knitting and purling, were garlands of red lights. The rooms inside were also illuminated with a soft, red light. Peering beyond one of the knitting women, we saw a large, softly-lit room partitioned into smaller cabins, just large enough to accommodate a bed. And as men walked by, the knitting women would invite them in with a wave or a smile.

So it's not just Lhasa or Xigatse, but even Zhangmu, just beyond our own scruffy, poor border, that had become mini-Patpongs. There was a dazzling array of consumer goods, discos, bars, nightclubs, restaurants, shops-and brothels. Kathmandu has perhaps half-a-dozen discos, tiny Zhangmu has close to ten. The fashionable Chinese women we saw came from the mainland, and most of their clients were Nepali merchants and traders.

So it's not just Lhasa or Xigatse, but even Zhangmu, just beyond our own scruffy, poor border, that had become mini-Patpongs. There was a dazzling array of consumer goods, discos, bars, nightclubs, restaurants, shops-and brothels. Kathmandu has perhaps half-a-dozen discos, tiny Zhangmu has close to ten. The fashionable Chinese women we saw came from the mainland, and most of their clients were Nepali merchants and traders. We returned to our lodge for dinner and then came out to really explore the irresistible and colourful red-light district of Zhangmu. It was now after 9 PM Nepal Time-past midnight in Zhangmu. We didn't have to go far. In the shop attached to our lodge, we saw the glow of a red bulb. The women inside beckoned to the men among us, but we moved on. The next time, two of our friends went in and returned a few minutes later smiling. The women had asked them to drink beer and hang out.

Walking on, we entered a place that advertised itself as a Night Club. On the second floor of this rather large but ancient-looking building was a disco. The "bouncers", the bartenders and waitstaff were all women. It looked as if the place was run entirely by women, but worldly-wise as we all were, we suspected that the real operators were men, lurking behind the scenes. Two women guided us to a sofa to listen to a man with a microphone lip-synching a slow, probably romantic, Chinese song on a \'videoke'. A few couples were dancing languidly. A Chinese woman asked us in Nepali what we would like to order. We asked for beer. As if on cue, the music changed to a fast-paced English song. We all got up and danced, and perhaps because of that the music continued to be western. After dancing some more, we sat down to rest and have another beer. The music switched back to dreamy, croony Chinese.

Walking on, we entered a place that advertised itself as a Night Club. On the second floor of this rather large but ancient-looking building was a disco. The "bouncers", the bartenders and waitstaff were all women. It looked as if the place was run entirely by women, but worldly-wise as we all were, we suspected that the real operators were men, lurking behind the scenes. Two women guided us to a sofa to listen to a man with a microphone lip-synching a slow, probably romantic, Chinese song on a \'videoke'. A few couples were dancing languidly. A Chinese woman asked us in Nepali what we would like to order. We asked for beer. As if on cue, the music changed to a fast-paced English song. We all got up and danced, and perhaps because of that the music continued to be western. After dancing some more, we sat down to rest and have another beer. The music switched back to dreamy, croony Chinese. A svelte girl in a short skirt asked one of our friends, sixty-year old Ganesh Man, to dance with her. The music was slow, and the angel put her hands on Ganesh Man's waist, teaching him to step and sway in time to the music. Despite his years, Ganesh Man was a quick learner and was soon dancing effortlessly. Very soon, the two were the only people left on the dance floor, as the rest of us watched indulgently. Ganesh Man is a simple farmer on the outskirts of Kathmandu, and we agreed among ourselves that this was perhaps the best fun he'd had in his life. When we left an hour later, Ganesh Man tipped the woman Rs 100.

As we were leaving, we discovered that the floor below was a brothel. A passage, perhaps three feet wide, led away from the stairs. There were Chinese women milling about. Our men friends wondered what was going on, so they went in, and I followed. On the right was a large room, once again curtained off into several smaller rooms with a bed each. Father down the passage, there were more women knitting sweaters and gossiping at the entrance of each cabin. In a single, large parlour, fashionably dressed women were playing mah-jong. I tried to strike up a conversation. Some appeared taken aback, others were simply angry. I got the distinct impression that they did not like women approaching them. When our male companions showed up, they were all smiles.

As we were leaving, we discovered that the floor below was a brothel. A passage, perhaps three feet wide, led away from the stairs. There were Chinese women milling about. Our men friends wondered what was going on, so they went in, and I followed. On the right was a large room, once again curtained off into several smaller rooms with a bed each. Father down the passage, there were more women knitting sweaters and gossiping at the entrance of each cabin. In a single, large parlour, fashionably dressed women were playing mah-jong. I tried to strike up a conversation. Some appeared taken aback, others were simply angry. I got the distinct impression that they did not like women approaching them. When our male companions showed up, they were all smiles. Some distance away from here, we saw another disco with a lot of Nepali men inside. It was dark, but crowded, the dance floor packed with Nepali men. Others were seated at tables, drinking and chatting with Chinese girls. Soon, a woman in a cheongsam made an announcement. The couples on the dance floor melted away, and on came young couples wearing a variety of traditional Chinese dresses. A fashion show! Keeping in mind the predominance of Nepali patrons, some models appeared in daura-suruwal and Nepali topi, and saris. It was so lively that it was easy to miss a crowd of local Tibetan women outside, tired from a hard day's work of loading and unloading trucks, watching people like us eating, drinking and enjoying ourselves.

In fact, it doesn't take long to realise in whose hands all the trade and commerce in Zhangmu is. In their ragged bakkhus and wispy braided hair, the Tibetans look less well off. Some Tibetan women use a single conch shell as a bracelet-the hand is inserted through the openings in the shell-women from the Amdo region of Tibet. The Amdo work in groups in cities as far away as Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou. In Zhangmu, they work loading and unloading the hundreds of trucks that arrive every day from various parts of China. These women seem a lot stronger than their men when it comes to lifting and carrying loads. Not long ago, the Amdo were all over Zhangmu, running businesses and doing all sorts of work, but their numbers are slowly dropping.

In fact, it doesn't take long to realise in whose hands all the trade and commerce in Zhangmu is. In their ragged bakkhus and wispy braided hair, the Tibetans look less well off. Some Tibetan women use a single conch shell as a bracelet-the hand is inserted through the openings in the shell-women from the Amdo region of Tibet. The Amdo work in groups in cities as far away as Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou. In Zhangmu, they work loading and unloading the hundreds of trucks that arrive every day from various parts of China. These women seem a lot stronger than their men when it comes to lifting and carrying loads. Not long ago, the Amdo were all over Zhangmu, running businesses and doing all sorts of work, but their numbers are slowly dropping. As we staggered back to our lodge around 1AM, Beijing/Zhangmu time (four in the morning across the river in Nepal) it came to me that if Kathmandu consumers or wholesalers wanted to buy fake Head & Shoulders shampoo or fake orgasms, they no longer had to travel to exotic-and expensive-Bangkok or Hong Kong, but that a capitalist paradise of cheaper consumption and ownership was right next door in Mao Zedong's Zhangmu.

In Khasa, getting rich is glorious again.