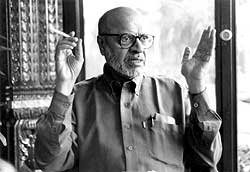

For the film aficionado Shyam Benegal needs no introduction. One of the major personalities of the \'new cinema' in India, at last count he had made 21 feature films, 45 documentaries, including the epic 53-hour Bharat Ek Khoj (Discovery of India), and over 1000 commercial film-lets. Such a wide-ranging oeuvre aside, he can also be credited for providing the first real breaks to such artistes as the late Smita Patil, Shabana Azmi, Girish Karnad, Om Puri and Amrish Puri. He has received several national and international awards for his films, apart from the top Indian civilian awards, the Padma Shree and the Padma Bhusan.

During the film director's recent visit to Kathmandu to chair the Jury at Film South Asia '01 held 4-7 October, Nihal Rodrigo met him over coffee, cappuccino and (many) cigarettes and asked about his vision of the cinema, the responses his films have evoked, and the relationship between film and literature.

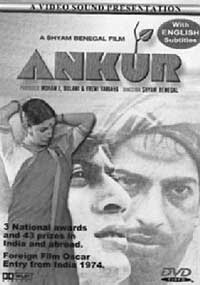

Your first film, Ankur, looked at social and gender discrimination in a feudalistic society in rural India. Two years later, in 1976, you came up with Manthan, dealing with social mobilisation and empowerment of rural dairy farmers and their struggle against exploitation. Latter films too deal with social issues that have largely been ignored by other filmmakers. To what extent do you believe can films bring about social and economic change in real life?

Your first film, Ankur, looked at social and gender discrimination in a feudalistic society in rural India. Two years later, in 1976, you came up with Manthan, dealing with social mobilisation and empowerment of rural dairy farmers and their struggle against exploitation. Latter films too deal with social issues that have largely been ignored by other filmmakers. To what extent do you believe can films bring about social and economic change in real life?

The cinema or individual films are not capable of really effecting huge political and social changes in India or anywhere else. But the film is a powerful medium for bringing to the fore, subjects which otherwise would be lost to public discourse. Cinema can give social urgency and highlight the need to deal with the plight of groups who have no lobbies. That is the primary thing the (politically and socially conscious) cinema can do. You have to work towards an attitudinal change. This must be preceded by a change in perception. It won't happen with one film. It is a process.

I have sought to reach out to audiences beyond those already conscious and aware - people of the same feather. Film must be engaging, engrossing to a very large number of people. Films must entertain. Popular acceptance and appeal is essential.

What precisely was the impact and reach, then, of what you sought to convey in your films-specially Manthan?

Ankur was commercially successful not only in India, but all over the world. But Manthan was a unique film in more than one respect. In the 1970s, the movement to establish milk cooperatives had begun in Gujarat spearheaded by Dr Verghese Kurien of the Indian National Dairy Development Board and involving about half-a-million dairy farmers. I had already made a documentary on the subject and gathered a great deal of research material. I discussed with Dr Kurien the possibility of making a commercially viable fiction film which would also have an important real story to tell. Dr Kurien agreed and suggested that the dairy farmers themselves be the producers-i.e. the financiers-of the film. Each member of the milk cooperative, half a million of them, contributed two rupees each. The funny thing is that not only was the film, therefore, produced by the farmers themselves, it was also popularised by them. Farmers travelled in lorries and buses from all over to see the film at the nearest town. It had a second usage as well. There were no video players then but with Super 8 and 16 mm portable projectors, spearhead teams went to villages in milk producing areas to engage them in dialogue as to how they could increase milk production, maximise their earnings and improve the breed of their cattle. The film was, therefore, very important to stimulate discussions. The film was seen by more people than any single film made in India. It was shown in over 150,000 villages in addition to the cinema circuits. It was a springboard to develop new cooperatives all over India. Today, twenty years later, the film is still being used.

Ankur was commercially successful not only in India, but all over the world. But Manthan was a unique film in more than one respect. In the 1970s, the movement to establish milk cooperatives had begun in Gujarat spearheaded by Dr Verghese Kurien of the Indian National Dairy Development Board and involving about half-a-million dairy farmers. I had already made a documentary on the subject and gathered a great deal of research material. I discussed with Dr Kurien the possibility of making a commercially viable fiction film which would also have an important real story to tell. Dr Kurien agreed and suggested that the dairy farmers themselves be the producers-i.e. the financiers-of the film. Each member of the milk cooperative, half a million of them, contributed two rupees each. The funny thing is that not only was the film, therefore, produced by the farmers themselves, it was also popularised by them. Farmers travelled in lorries and buses from all over to see the film at the nearest town. It had a second usage as well. There were no video players then but with Super 8 and 16 mm portable projectors, spearhead teams went to villages in milk producing areas to engage them in dialogue as to how they could increase milk production, maximise their earnings and improve the breed of their cattle. The film was, therefore, very important to stimulate discussions. The film was seen by more people than any single film made in India. It was shown in over 150,000 villages in addition to the cinema circuits. It was a springboard to develop new cooperatives all over India. Today, twenty years later, the film is still being used.

Susman, made in 1986, dealt with what is the second largest trained human resource in India-the handloom and textile workers. However, the film did not have the same popularity and spread as Manthan but helped to bring to the surface an issue which involved such a large section of the population and a cottage industry, and an art that was threatened.  Samar (1998) was a comedy on caste prejudice that could make a lot of people uncomfortable and unhappy. Its commercial release has been held up and I have been agitating for its release.

Samar (1998) was a comedy on caste prejudice that could make a lot of people uncomfortable and unhappy. Its commercial release has been held up and I have been agitating for its release.

Antarnaad, made in 1999, is a film based on the teachings of Parwan Shastri, who lectured on interpretations of the Gita. According to Shastri, the real cause of the vicious cycle of under-development was a lack of self-esteem among marginalised people which inhibits the emergence of their latent talent and capabilities. Thousands of village communities in Gujarat and Maharashtra were transformed by the Swadhyayi concept, which shuns charity hand-outs. Philanthropy is not their idea. The basic concept is that you create wealth by sharing-not by giving or selling your surplus, but by sharing what you have.

More recently, Hari Bhari last year (which starred Shabana Azmi and Nandita Das) took up the controversial issue of fertility and family planning. Antarnaad and Hari Bhari have had successful commercial runs.

Given your reputation for making films which take on challenging larger social and political themes, have you attempted films which are personal and introspective, and which probe deeply into the individual psyche?  Deep psychological enquiry is, to some extent, a middle-class luxury as far as cinema is concerned. This is particularly so for India where there are so many larger, more pressing concerns around. I would not say the same is true of literature which is more personal and inwardly probing.

Deep psychological enquiry is, to some extent, a middle-class luxury as far as cinema is concerned. This is particularly so for India where there are so many larger, more pressing concerns around. I would not say the same is true of literature which is more personal and inwardly probing.

Take my film Suraj Ka Satwan Ghoda (1992). It is based on a Hindi literary classic of Dharamabeer Bharati with many interesting aspects in it. A young man tells three stories to define what love is. They are about three different women with whom he has had relationships, first as a pre-pubescent, then as an adolescent and thirdly as a mature adult. But all these relationships are happening at the same time, simultaneously. There is no time difference. He knows the three girls at the same time. As human beings, we have this inner psychology and a way of creating a self-image and behaviour with people at certain moments of that relationship. This behaviour freezes in that position. For example, you sometimes behave with your father even in your adulthood as though you were still 12 years old.

That film was a difficult exercise.

Literature has the ability to deal with time and space in a way that cinema finds difficult to do. Cinema concretises the image. Symbols and emblems become very definite and concrete in film unlike in literature. Words are abstract, but when put together in literature, they have an associational context. Spaces between words are filled up by the reader in whom things are evoked through his own associations and imagination. Cinema does not always have that associational capability. The evocativeness of literature is very difficult to produce in cinema. In cinema, you see everything through the director's eye and that becomes totally subjective.

You have made both documentary and feature films. How different is one from the other?

The documentary film attracts filmmakers who have something to say-more than the feature film. Documentaries by and large tend to deal with the real stuff of life, reality directly observed. Much of what you do in documentaries is not necessarily within your control. When you make a documentary "about" something, you are not in the real thick of it. In fiction films, you can get into characters, into their motivation and into various things, even though you are subjective. You bring an interiority into the subject and to be able to do so gives you in fact a greater sense of reality than when you merely observe and reproduce reality. Film fictionalised from real life tends to give you great opportunities to present such a greater reality.

The documentary film attracts filmmakers who have something to say-more than the feature film. Documentaries by and large tend to deal with the real stuff of life, reality directly observed. Much of what you do in documentaries is not necessarily within your control. When you make a documentary "about" something, you are not in the real thick of it. In fiction films, you can get into characters, into their motivation and into various things, even though you are subjective. You bring an interiority into the subject and to be able to do so gives you in fact a greater sense of reality than when you merely observe and reproduce reality. Film fictionalised from real life tends to give you great opportunities to present such a greater reality.

Who are the film directors you like the most?

My tastes are very catholic. Among the older American directors, I like John Ford. Among contemporary US directors, Martin Scorcese and Coppola. In Japan, the great directors Kurosawa and Ozu. In Italy, Fellini and Pasolini. In India, Satyajit Ray, of course, and in the popular cinema, Ritwik Ghatak. I like also in the popular Hindi cinema, Mehboob and Guru Dutt; in the popular Tamil cinema, Mani Ratnam. Also Adoor Gopalakrishnan and Ritupatno Ghosh is a marvellous Bengali director. With all these directors, you can hear their voice in their films.